Entering the Lassoverse: When Conflict-Free Works

Ted Lasso does something that is normally a fatal flaw, but it works because it’s purposeful.

NEW STANDARD DISCLAIMER: This newsletter aggressively spoils things.

NOT too long ago I wrote about two entertainments that made the critical error of treating conflict like a irritation best done away with as quickly as possible (both under the steady hand of the most boring of all showrunners, Julian Fellowes1). In both The Gilded Age and Downton Abbey: The New Era, Fellowes carefully avoided any sort of lingering conflict: Problems were introduced, then almost immediately dealt with and sent packing so he could get on with adoring the costumes and implying that people who lived more than a century ago were surprisingly progressive2.

Conflict is the gas that drives a story, so watering it down until nothing sparks in its presence is always going to be a mistake. Except, of course, when it isn’t, because writing doesn’t actually have rules so much as a collection of general guidelines and best practices3.

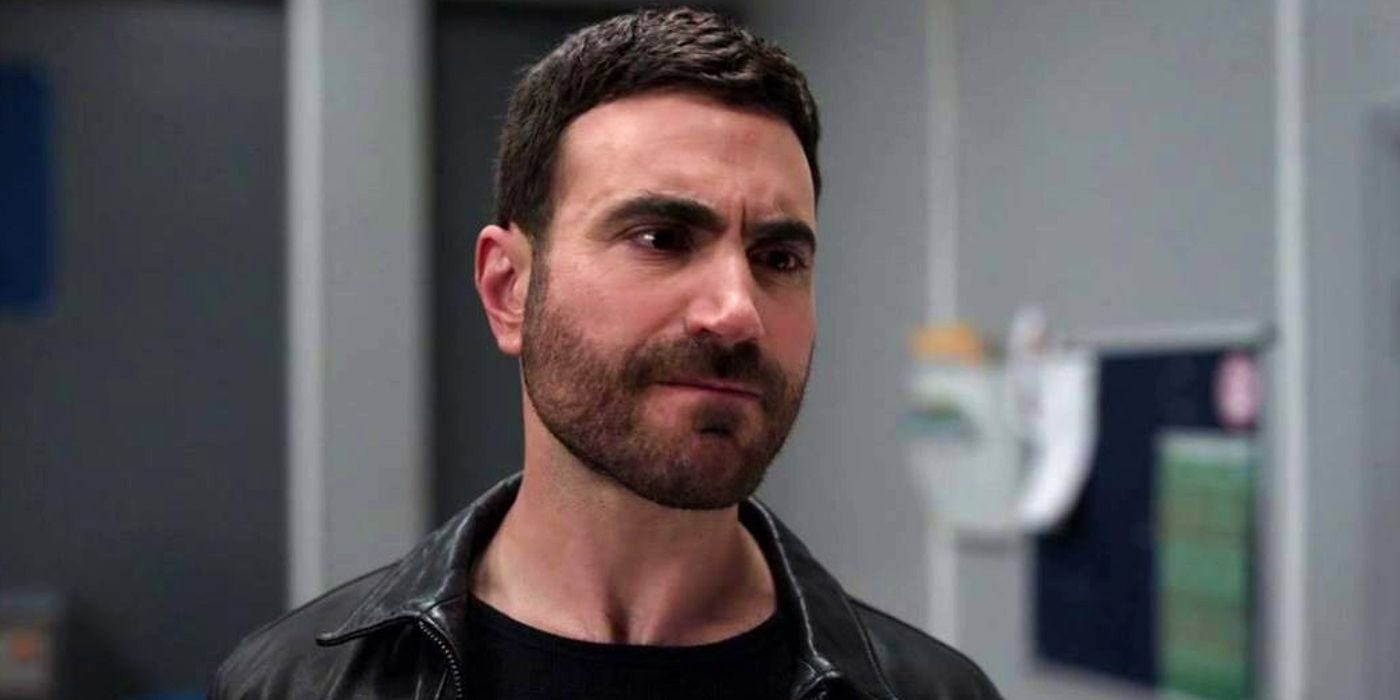

Case in point: Ted Lasso, a show so nice and sweet you get tooth decay watching it4. Ted Lasso never met a conflict it can’t defuse almost immediately, which would normally be ringing my BAD WRITING bell. Yet, it works, because Ted Lasso is intentional about it5.

BELIEVE

Ted Lasso is a show where conflict goes to die. Every single episode contains an example of an extremely temporary conflict, whether it’s an antagonistic interview with a sharp reporter that could result in a humiliating profile or an aging soccer star’s desire to take it slow with a new romance being misinterpreted as reluctance6. Even the major conflict arcs of the season resolve relatively easily—in season one, for sweet’s sake, the owner of the team admits to Ted that she hired him because he knew nothing about soccer and worked to help him fail, and his reaction is to forgive her and everyone goes back to being terribly nice7.

Normally, I am very much against things being terribly nice8, and I would complain about this lack of real conflict. Except ... it works.

Every character in the wider Lassoverse is redeemable. No matter what temporary evil they are engaged in, there is either a justification for their decisions and a positive heel turn on the horizon. Every villain in the show rapidly decays into an ally—and I believe even the two villains who haven’t yet received redemption arcs (Rupert and Nate) will enjoy one before the series ends. Rebecca comes to regret her schemes to ruin the team and use Ted, Jamie exhibits flashes of a conscience and appreciates Ted’s kindly advice more than he lets on (and eventually takes Ted’s coaching to heart as well), and even jealous Roy Kent quickly gets past his hatred of Jamie when he’s beginning his romance with Keeley, one of the speediest examples of a conflict vanishing before a viewer’s eyes that I’ve ever seen. Sometimes conflicts vanish on these shows so fast they’re resolved before they’re introduced.

But it works. It works because the show takes place in a universe where goodness is presumed. It’s a distinct choice. The Lassoverse is a place where everyone is fundamentally good and transgressions are temporary9. It’s part of the essential charm of the show, the comfort-food aspect of it. In real life there are people who will be assholes to you all the time forever. In the Lassoverse, they will all eventually realize how shitty they’ve been and have regrets. That is surprisingly powerful fiction.

Intentionality

That intentionality is what saves it. In shows with worse writing, like Downton Abbey, conflicts melt away like ice in the sun primarily because the writers have zero interest in their own story and can’t wait to get past whatever boring conflict they’ve concocted this time10. But in Ted Lasso the conflicts are done away with because that’s the whole point of the character and the show: If you’re a decent person and put in the work, everything resolves itself.

That makes the quick resolution of conflicts part of the code underlying the stories, so it doesn’t read as lazy. The conflicts are treated more like the mysteries on weekly crime shows—something that’s introduced at the beginning of each episode that you know will be resolved by the end of the hour—or within a few episodes if it’s a more ambitious story arc (e.g., Rebecca’s campaign to destroy the team11). But you know going in that it will be resolved, and pretty fast, so it doesn’t feel slapdash.

I have an ongoing argument with a writer friend who has some pretty hard and fast rules about what can and can’t work in a story; I argue that anything can work if you approach it the right way and have the writing skill to tackle it. I think Ted Lasso is proof that I’m right—this is a writer’s room that is actively undermining their own conflicts, which should be a problem. But it isn’t, because it’s purposeful. The show wants to be a feel-good bop, and for that to happen conflicts cannot ever be insurmountable.

Did it take me this long to sign up for Apple TV+ and watch this show? Yes, because it grinds my gears that Apple has all the money in the world and still expects me to give them some of mine. This seems inherently unfair.

Next week: ‘Alice Darling’ and the importance of rhythm.

Fellowes’ work will someday be studied for its exhaustive investigation into the capitalist horrorshow phenomenon of “servants who become ridiculously house proud over homes they do not actually own themselves.”

It will not surprise me at all if the next installment of the Downton Abbey franchise involves a spirited campaign to have Lady Crawley elected Prime Minister because why shouldn’t ladies be Prime Ministers in 1925?

Do you see what I did there? I am a genius.

The show is generally so nice and upbeat that the regular forays into Ted’s trauma and anxiety attacks feels like an entirely different show.

Unlike when I write a tense, taut thriller story and everyone congratulates me on a pitch-perfect parody of tense, taut thrillers and I immediately pivot to exhibiting relief that everyone knew I was trying to be funny <bursts into tears>.

Weirdly, this is actually closer to real life in many ways. Too many shows rely on characters simply not saying the most basic and obvious things to each other for no other reason than to gin up some fake conflict and string it out for a while — the ole’ Three’s Company gambit. Gosh, I’m old.

Even more perplexing in the modern world of pop entertainment, the characters on Ted Lasso actually seem to remain changed by their experience. After her comeuppance and evolution in Season One, Rebecca remains a fundamentally decent ally throughout Season Two, instead of instantly reverting to her semi-villainous ways, which is what most other shows would have done, because shows—esepcailly situation comedies—love characters to always play the same role.

This is why I verbally abuse everyone I meet on a constant basis. To keep my edge.

Although I appreciate the fact that the show remains committed to Ted being kind of clueless about soccer and not a particularly good coach from a game standpoint. This sort of thing gives incompetents like me hope.

Usually involving servants entering a room they are forbidden from entering, threatening the downfall of the English Class System.

Stolen, I firmly believe, from the all time classic Major League.

"Stolen, I firmly believe, from the all time classic Major League."

you certainly have good taste in baseball movies.

Ted Lasso is my favorite show of all time, bar none precisely because it is feel good, funny exploration of the better bits of humanity. I am full up on our darkness. Also, love the football/ community aspects of this show. It is truly beautiful.