‘Civil War’: Too Smart for Its Own Good

Alex Garland makes an audacious, smart writing decision that proceeds to undermine the entire film.

NEW STANDARD DISCLAIMER: This newsletter aggressively spoils things.

I swear, sometimes the hardest thing in the world is to just start watching something1. There it is, a little square on your screen—you’ve heard good things, you’re intrigued—and all you have to do is press play and you can experience an entertainment! It is truly a time to be alive. But you ... just keep not doing it. Every time you turn on the TV, there it is—a little lower on the list each time, slowly dying because you’re starving it of the attention it needs to survive2.

I’ve had this situation for years at a time—someday, I swear, I will watch Letterkenny3—but recently I had a brief bout of it with Civil War, Alex Garland’s latest work of grim mindfuckery. It sounded interesting, it had solid reviews, it starred ace performers. And yet, every time my finger roamed towards the button I read a book instead4.

When I finally got around to it, pushing through my internal resistance like a marathoner at mile 26, I enjoyed it in that way you enjoy Alex Garland films: Slightly uncomfortably. It’s a well-made film, and an interesting one. And Garland makes a writing choice that is actually kind of brilliant—in the abstract. Unfortunately that brilliant decision prevents the film from being an actual success5.

Don’t Let Them Kill Me

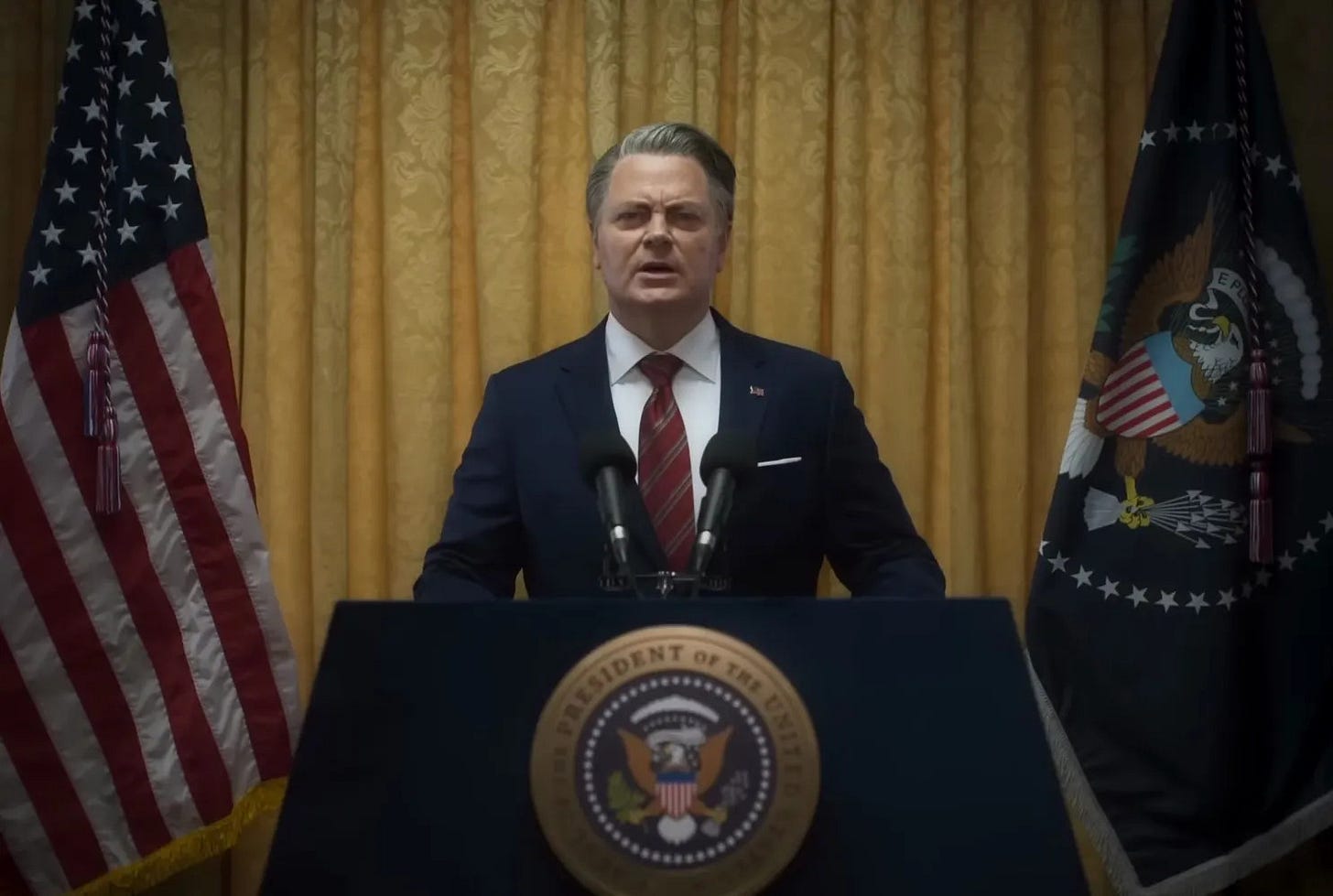

Civil War is set in an indeterminate future United States embroiled in, yes, a Civil War. California and Texas have formed the Western Forces (loosely allied with Florida6) against the United States government, personified by the unnamed President (Nick Offerman), who is holed up in Washington D.C. serving out an embattled third term as the Western Forces close in7. Photographer Lee (Kirsten Dunst), journalists Joel (Wagner Moura) and Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) are joined by young photojournalist Jessie (Cailee Spaeny) in a road trip to D.C. in hopes of interviewing the President before D.C. falls8.

The trip to D.C. is hellish—the roads are simultaneously eerily empty and incredibly dangerous, especially as not everyone loves the press—though you will never know why, exactly, or what each side is fighting for, exactly. Garland’s genius-cum-disastrous decision is the choice to exclude any sort of coherent politics or any identifiable ideologies from the story9. You are given zero information on the why and how of the war—what prompted the rebellion? What does Nick Offerman’s President stand for? You can’t know. There is simply zero information.

This isn’t cowardice or a reluctance to trigger half your potential audience, however, this is a narrative choice. Garland’s not actually interested in Civil War or American politics or any of that. He’s interested in journalists, the kind of people who will watch someone die in front of them and take a photo of it. Terrible things happen in this film, but the journalists at its heart just keep snapping photos. The key is, the main characters don’t care about the politics. They don’t know, or want to know, the why or the reasons. At one point Lee literally says “We don't ask. We record so other people ask.” They may not know much about it, in fact—all they know or care about is that there is news to be photographed, quotes to be gotten, scoops to be won.

The decision to withhold any sort of political context from the audience is about aligning us with the characters. We replicate their experience—they operate in a vacuum where the only thing that matters is the visual, is being in the right place when news happens. And so do we. It’s a smart writing trick, really, except for the fact that it kind of ruins the movie10.

What Kind Of American Are You

You can tell Garland is playing this trick because he purposefully muddies the water for you. Offerman’s president has no name and makes only the most broadly patriotic speeches you might expect from a chief executive watching a rebel army approach, but he’s a broad physical match to certain recent politicians, and the reference to a third term marks him as a bad actor in terms of American democracy. The alliance between California and Texas doesn’t make much sense in the current landscape, and throwing in Florida really makes it hard to parse11. Which is intentional: Garland doesn’t want you to understand, because his journalists don’t care, and he doesn’t want you to, either12.

The problem, though, is that this decisions renders everything on the screen abstract. The film is structured as a series of vignettes; our journalists embed with some street fighters, get pinned by a sniper, shop at a weirdly idyllic small town seemingly untouched by the war, and experience a nightmare at the hands of a racist, bullying soldier. But none of it means much, because none of it has any weight. The lack of interest in anything but the story or the image or the quote leaves everything feeling meaningless.

This might be the intention; the final sequence sees Lee step in front of a bullet to save Jessie, who she sees as a younger version of herself. And Jessie and Joel just leave Lee there, crumpled on the floor, dead, in order to get the quote and the photo of the President as he’s summarily executed by the Western Forces13. In the end, not even Lee matters—only the news. Garland might not want us to care about his characters, either, but this makes it damn hard to care about the film itself.

Luckily every single photo I’ve ever taken in my life is slightly blurry and composed as if I only recently gained the ability to see, and journalism is a lot of work I don’t care to do, so I’ll never be a dispassionate observer. I’ll be the guy screaming in terror as he runs past you while evacuating the city14.

NEXT WEEK: It’s What’s Inside and the unstressed detail.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing to my paid fiction Substack, Writing Without Rules: From the Notebook!

Also: Matching socks. I’ve pretty much given up at this point. Just call me Clown Feet. Is Just Call Me Clown Feet the title of my memoir? YES!

I’ve spent my whole life pointlessly anthropomorphizing inanimate objects, and I’m not about to stop now. I will apologize to my pens before I throw them away until my dying breath.

Spoiler alert: Probably not.

Or maybe ate a burrito, my memory is unclear. I just find them in my pockets, sometimes. Is Burrito Boy: The Corpulent Story of Jeff Somers the title of my memoir? Lord, I hope not.

One sympathizes. Every brilliant decision I’ve ever made has prevented me from being an actual success. There might be a lesson in that, but I refuse to learn it.

I like to imagine the entire state of Florida is just Wildcarding its way through the Civil War like a guy with a mullet drinking a case of beer while he airboats through a swamp.

The standard template for fictional U.S. presidents remains a square-headed white man, and probably will for some time. The template for U.S. presidents in sci-fi stories is usually either a person of color or a lady, though, to show how crazy the story’s premise is. We have a way to go.

There’s a clear implication that Joel invites Jessie along at least in part because he wants to sleep with her, which is all well and good except Cailee Spaeny looks like she’s a traumatized 12-year old.

I do the same thing in my writing, but I do it because I’m an idiot who doesn’t understand anything. Is An Idiot Who Doesn’t Understand Anything the title of my memoir? Maybe the subtitle.

Just like me drinking a fifth of moonshine before sitting down to write a novel is a smart writing trick, until I actually read what I wrote the next day while in the hospital.

Throwing in Florida always causes chaos, in any context, of course.

Lucky for him it’s very, very easy for me not to care about things. With the exception of my cats. I will walk through fire for my cats. Is I Will Walk Through Fire for My Cats the title of my memoir? It sure should be.

Any time I see Nick Offerman in a straight, dramatic role I am confused and alarmed. I keep expecting him to start riffing on how to build a chair with your bare hands.

With five cats riding on his shoulders and a bottle of whiskey by way of luggage.

I agree completely with your analysis. It rendered everything almost anyone did kind of flat, even the crazy violence. It just made me go, "Oh, that's terrible!", without really FEELING it, you know? HOWEVER, the moviemaking - esp that last sequence - was really terrific.